note: These words were first written more than a month ago, while still at Standing Rock. They were completed as the final camps closed last week. While in the Dakotas, I was taught to ask the forgiveness of my elders, if my words were spoken in any way that is false. I ask that forgiveness now. In many ways, I am writing about subjects of which I am a new student. They represent a growing understanding of who I am, and who we are. I welcome feedback, corrections and suggestions.

They are the words of my heart.

_____

There is a great deal to share. Perhaps too much. When stories remain buried for so long, the work of pulling them to the surface, can be a painful and provoking journey. Though I’m only a few sentences in, this seems to be true tonight.

The wind is rushing through Standing Rock with great fury. Months ago, wind like this would have left a trail of destruction in its wake. Tents overturned, kitchens scattered across the plains, blankets exposed to a moisture that never seems to dry. Today, a camp hardened by a hundred weeks of survival, stands strong against the wind. When she roars, we simply hunker down and wait for her to rest.

A great deal has changed, since tents first lined the horizon a year ago. The resistance of Standing Rock has moved and shifted, adapting moment by moment, to a physical environment that threatens those not ready to survive, and a political environment that for Native Americans, has often been far more lethal.

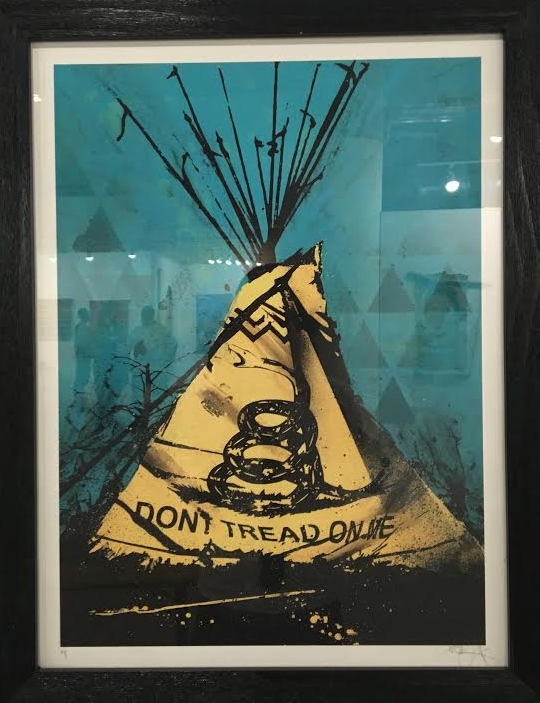

My first, and perhaps most vivid memory from my time here, was driving up to the entrance of Oceti Sakowin, often known as main camp. My old pickup had crossed hundreds of miles of Great Plains, a smattering of small towns, farms and cattle ranches, before turning a corner to find a small hill, standing above hundreds of tents, tipis, yurts, wigwams and whatever structures could be built with tarps and 2x4s. It was striking, a small glimpse into how this land has been inhabited for thousands of years. Most striking of all, were the flags.

Hundreds of flags lined the highway guiding us into camp. Flags representing sovereign nations from across this land.

Flags I had never seen.

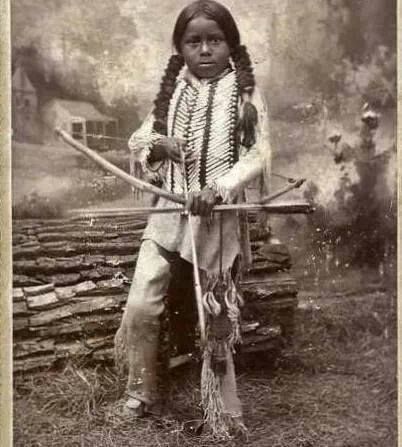

I didn’t thrive in the classroom, but I have been studying the ways of the world for much of my thirty-four years. How is it possible, that I had never seen any of these flags? Sovereign nations, each with internationally recognized treaties, and a Tribal Government. And yet, with years of higher education, I had never learned anything meaningful about who they are, where they live, how they live, or why. Never seen a true symbolic representation of who our nation is. As the days became weeks, and the weeks became months, it became clear that if I had never seen these flags, I had also never seen a real map. Surely I knew the border between Kansas and Nebraska. But I did not know the boundary between Kansas and the Potawatomi Nations. Or the boundary between North Dakota and the Standing Rock Sioux. Or hundreds of other sovereign nations, within this nation.

The morning after driving in and setting up camp, I walked past a young man working to raise a tipi. Ready to work and curious to learn, I offered to help. Hours later, the structure was up, and we were invited inside for dinner. A small group of us spent the evening around a fire, smoking tobacco, sipping soup warmed by the flames, and telling old stories. Another young man was there from Canada, and had been raised traditionally Haudenosaunee. The French called them Iroquois, and we know them as such. But the name may have originally meant “the killer people,” and was used, as many of our names have been for those who have always been here, to describe an enemy.

While at home, he grew up on traditional songs, thousands of years old. From his earliest ages, he was raised to respect the Great Law Of Peace, a gift of wisdom and laws, that the best of ours have often imitated without acknowledging their source. And he was taught the history of his people. In between his traditional upbringing, he found his way to the streets of Toronto. Among the city he discovered the underground hip-hop and punk music that raised a generation. He found art and design that expressed a pain he felt within. Below his long traditional braids, jeans sagged over high tops, proudly showing his colors.

That night, he spoke of the original paths that moved east-to-west and west-to-east across this continent. The trails and walkways, created by animals over a millennia. Those paths were followed by Indigenous people, widening and hardening them ever so slightly. The original walkers would eventually, after thousands of years, share those trails with the European trackers who first ventured west. Their horses and mules making the trails a bit wider. A bit harder. In time, the trackers would sell their maps of the trails to the Calvary. Suddenly, a mass of horses, wagons and humans, would begin carving wide tracks across the continent. Today, many of our highways run across those very same trails. Even now, he shared as the cold pressed against the tipi walls, wind patterns follow our road patterns, reflecting the intuitive intelligence of the animals who first paved them.

It is a history that’s largely erased. In town after town, we see generals and explorers, elevated and celebrated. While those they conquered remain unnamed.

Last year, a significant amount of human energy was spent drawing lines in the sand. Are you on this side? Or that side? I felt the pressure in many conversations, and in the culture at large. Pick a side. The question finding its way into so much of our conversation. I remember standing in Philadelphia, surrounded by the spectacle of our democracy, and asking — is this my side?

As a young man, I walked into the democratic republic of Congo, naive and optimistic. Surely, there must be solutions to these, the gravest of human challenges. For many years, we collected data and intelligence. Interrogated the power structure, interviewed the power brokers, and built relationships with those similarly concerned. We built mind maps, and strategic plans. Coalitions and campaigns. Briefs and presentations. Movements and energy.

Years later, I returned to the country with new context. Hopeful surely, for friends and loved ones, but more aware of the land. Of her history and pain. Walking down a row of large, elegant homes, beautifully built along the lakeside for the Belgian colonizers, and now generally filled with white westerners — served and waited on by black locals — it became clear that the great obstacle to peace was neither rebels nor warlords. Not protests or social unrest. The great obstacle to peace is now, as it has been for many centuries; colonialism.

War in the region has persisted for decades, largely fueled by those who wish to control a land, brimming with natural resources. Global wars. Wars that have claimed the lives of some six million people. Over the years, the victims have been everyone and everything, living in the center of Africa’s heartland, as mass violence ultimately protects no-one and nothing. The victors are all of us who use modern technology, or are protected by advanced weaponry. Technology that requires precious minerals. Minerals that often come from Congo. Those defeated have generally died in the shadows of secrecy. A genocide buried.

I remember when we built our first website, to campaign for peace in Congo. One of the pages was a timeline, detailing the history of the region. We worked hard to be meticulous, and get every detail right, while using the simplest possible language.

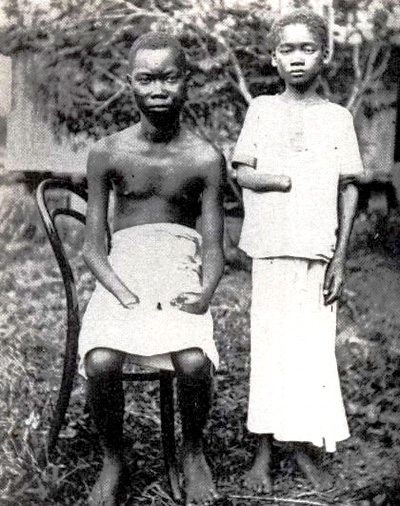

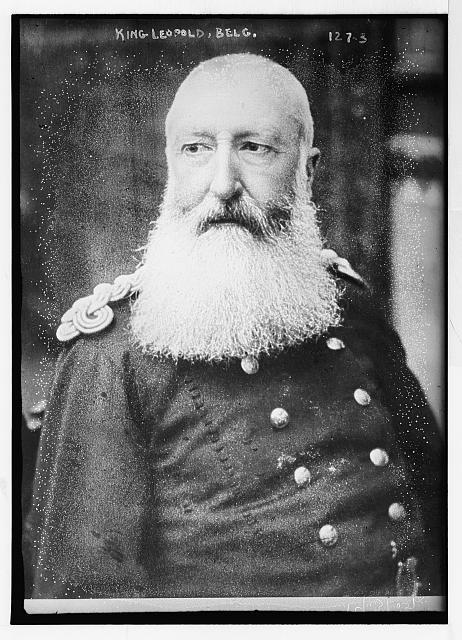

A few days later, I woke up to a scathing email from a young Congolese activist. His words were fire, and I didn’t know how to respond to such indignation. He was incensed that our timeline had begun the history of Congo, in the 1880’s. When King Leopold first began conquering and colonizing. It would take me a great many years to understand the depth of the insult. Of course a white man, educated in largely white institutions, had begun the history of an African nation, on the year a white man had begun his reign. At the time, there were some twenty million people living in Congo. Many living traditionally, in their indigenous way. Within twenty years, there were some ten million Congolese still alive. In King Leopold’s wild scramble for ivory and rubber, half the country had been killed. As the rise of the smartphone fueled a silent genocide in the Information Age, the rise of the automobile fueled a genocide, to pave the road toward industrial revolution.

In order to preserve bullets, a directive was given to the colonizing soldiers. For every bullet shot, a hand must be collected as proof of death. Millions of hands were collected. It is a symbol of one of humanity’s greatest crimes. And yet today, one can walk into a cafe in Antwerp, the capital city of Belgium, and order a delicate treat. Chocolate hands. If you’d like, you can order the Antwerpse Handjes online and have them delivered to your door.

When I first learned of this, I was disgusted. How could the Belgians be so blind, I asked. Do they not know that so many of their great boulevards and museums, palaces and universities, were built with the fortunes of genocide? Do they not see, that their countries wealth, has been created from vast exploitation and theft?

At the time, I had not fully considered our own traditions. Had not fully understood that Christopher Columbus was among the most savage killers in history. And yet, we celebrate him as our founder, do we not ?

Today, the former homes of the Belgian colonists in Congo are largely occupied by aid workers, NGOs and religious organizations. Well-meaning westerners, largely of European descent, intent to do some good in a place of so many challenges. Their presence often brings lifesaving aid, to those who need it most. It also brings inflation.

Coming from abundant economies, they are generally able to pay more than the locals. So the wealthy Congolese families leave the nicest homes, and move into the middle class homes. The middle class families leave, and move into the poor communities. And many of the poor communities simply become homeless. It is the smallest of insights, into a global system that continues to conquer, profit, and exploit — at all costs.

When Columbus first landed in Hispaniola, he found a community of people, known as the Arawaks. At the time, there were more than a million Arawaks, living on what we now call Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Within a century, there were no longer any Arawaks alive on the island. The first annihilation of our connected continents had completed itself. Their songs, their prayers, their wisdom and knowledge, were gone.

Soon after, a contingency of Spaniards sailed from Hispaniola to what is now South Carolina. There they captured seventy people, indigenous to this land, locked them in chains, and brought them to the King of Spain. Thus, the very first action of a European on this soil, was to make free men slaves.

The king of Spain rejected the gift, knowing a war with the indigenous people we called Indians, could not be won at this time. The Spaniards returned the natives, but the scars of the shackles were left on the wrists of the original Americans.

Some time later, another contingent of Spaniards arrived, but this time, they carried with them two hundred African slaves. After landing in South Carolina, they founded San Miguel de Guadalupe — the first cross continental settlement of mainland America.

Some say the seventy natives who had been previously enslaved, watched the settlement grow, waiting for the right moment to strike. When the leader of the colony died, and different factions were fighting for control, fires began burning across camp. Amidst the confusion, the natives rescued the Africans, and allowed the Spaniards to wallow in the wake of destruction. With no leader, and no slaves; the settlement eventually began to die. Those who survived, went home.

It would be nearly a hundred years before the Mayflower arrived. For a century, the beginnings of America were fostered, as Red and Black survived together. Lived together. Shared together. If there is to be a beginning to our land, let it always be known, that those beginnings were dark in their skin tone, and free in their being.

An insatiable hunger, for land and precious resources, drove Western Europe further than anyone imagined possible. Over the next three centuries, eleven countries, all predominantly white, all predominantly Christian or Catholic, and all employing tactics of totalitarian agriculture, conquered 78% of the planet.

Stop for a moment. Take a breath. Consider that number. Eleven countries, conquered seventy eight percent of the world.

Their expansion was driven, in part, by the natural scarcity of the regions they inhabited. If you are white, you are likely from the northern regions of the world, where food can only be grown for a limited number of months each year. In such an environment, the natural value system would be built around three dominating needs for survival. Measuring. Hoarding. Conquering.

To survive long winters, northern European cultures learned to meticulously measure their resources. They learned to store those resources at scale, over long periods of time. And if those resources ran low, they learned to conquer all who stood in their way of taking more.

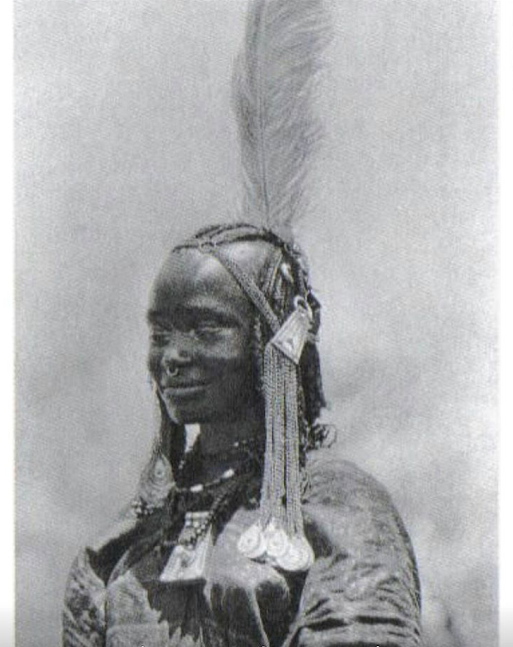

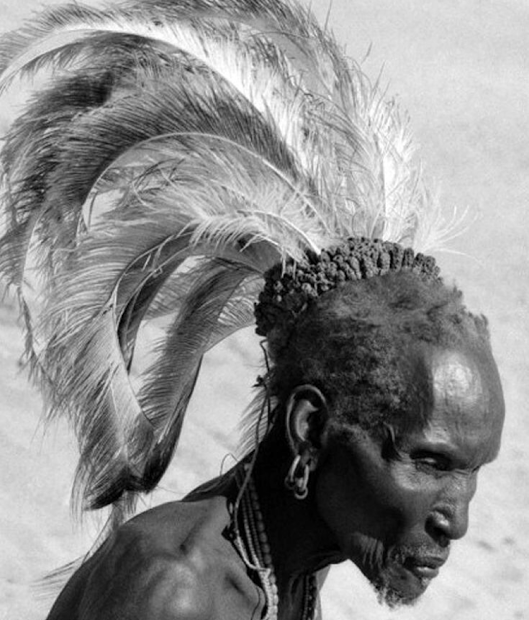

For many other cultures around the world, food was collected continuously, through hunting, gathering and gardening. These cultures were often more egalitarian, often matriarchal, and spent tremendous amounts of time focused on tradition, art, ceremony, community, storytelling, dance, music, sex, spirituality, family and prayer.

While Western Europe conquered vast swaths of the earth, the majority of humanity was then forced to live within a political, economic, and military framework of a very specific people. Who had come to their conclusions, in a very specific context. This expansion for food and resources grew, to include an unending desire for gold and silver, followed by iron, tin, copper, sugar, coffee, tobacco, tea, spices, rubber, ivory, and then eventually coal, oil, precious minerals, and more recently, water.

This hunger built the American railroad. Driven by a dream called Manifest Destiny — the belief that God had called the white man to go from sea to shining sea with a message of Democracy, Commerce, and Civilization — we swept the continent. When we finally reached the western shore, after incalculable deaths and a genocide matched only by our cousins to the south, we continued to spread the Good News from sea to shining sea. Only this time we began at the Pacific, and continued the long way around.

There are few corners on earth today, where a person of light complexion is not treated better than a person of dark complexion. Whether in Haiti or India, Congo or Thailand, the Netherlands or New Orleans, the dogma of white supremacy has found its way into every crevice of land that has been forced to participate in this colonial system. As Jomo Kenyatta, the first President of Independent Kenya said, “When the missionaries arrived, the Africans had the land and they had the Bible. They taught how to pray with our eyes closed. When we opened them, they had the land and we had the Bible.” The confluence of Capitalism, Christianity, and White Supremacy has resulted in a profound theft, so vast, later generations would scarcely recall that it was ever any other way.

Of course, western economists wax poetic about the great economic progress of our age. Through free markets and free societies, we are told, people are lifting themselves from poverty. India is often used as an example, detailing the shifts in lifestyle for some billion people. What we are not told, is that before the British colonized India, they had the fifth largest economy in the world. After colonialism, they were 95th. While we are told that prosperity comes with conformity, what I hear repeated in so many corners of oppression, is that prosperity is the result of sovereignty. The capacity of a people to self-determine. To self-govern. To find their own fate. Such is freedom. Such is liberty. And such is irreversibly counter to colonial rule.

In 1960, seventeen African nations had their first election in history. A great wave of democratic movements opposed their colonial overlords, demanding freedom for their people. Patrice Lumumba was elected the first Prime Minster of Congo. In his defiant speech to the Belgian government — a speech some believe led to his assassination by the CIA — he said, “I know and I feel in my heart, that sooner or later my people will rid themselves of all their enemies, both internal and external, and they will rise together as one man to say no to the degradation and shame of colonialism, and regain their dignity in the clear light of the sun.”

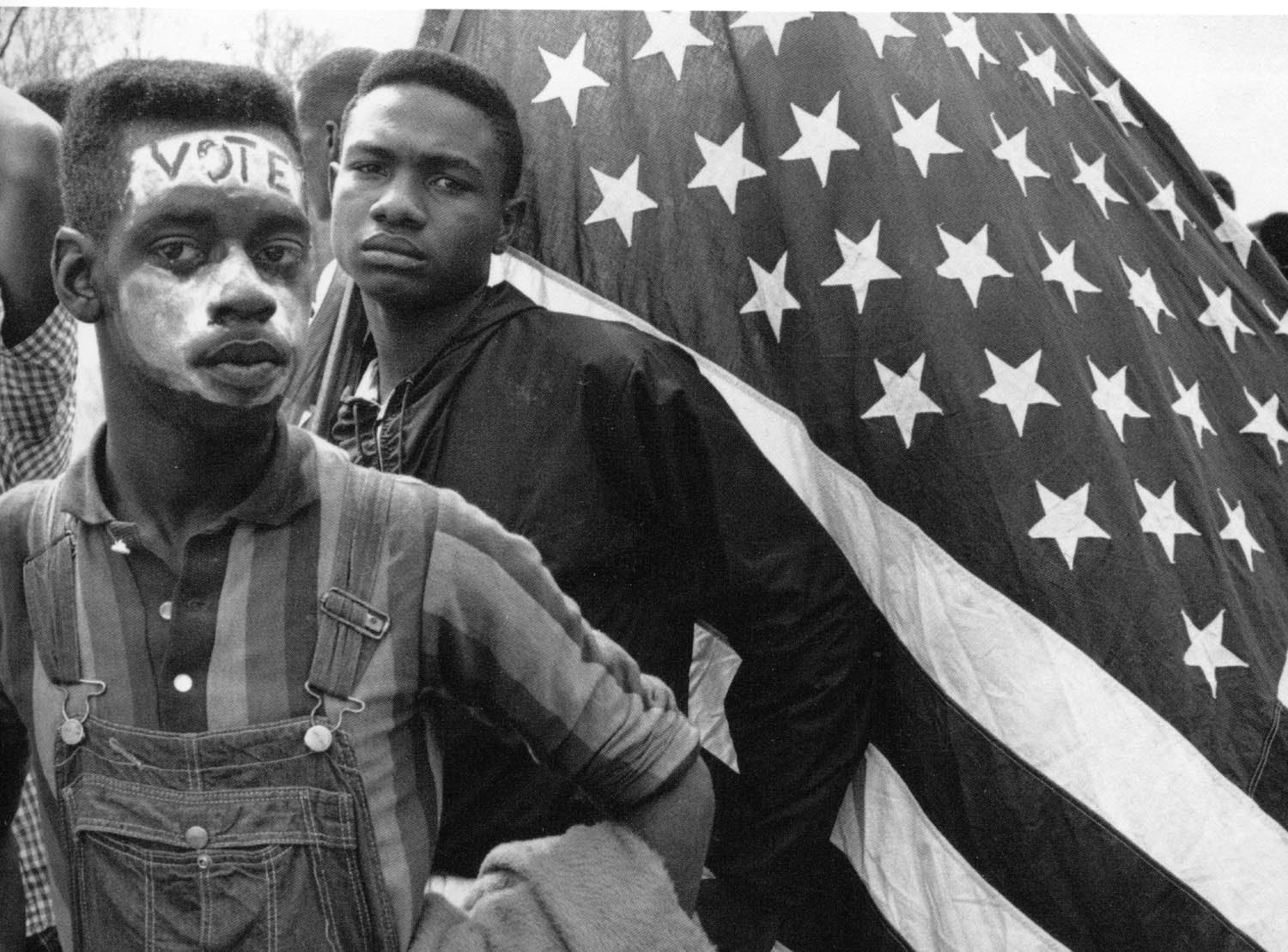

His speech was a rallying cry, for billions across the globe. Malcom X called him the greatest black man who ever walked the African continent. His message is repeated today by a mass of humanity, largely of darker complexion, rising up in revolution.

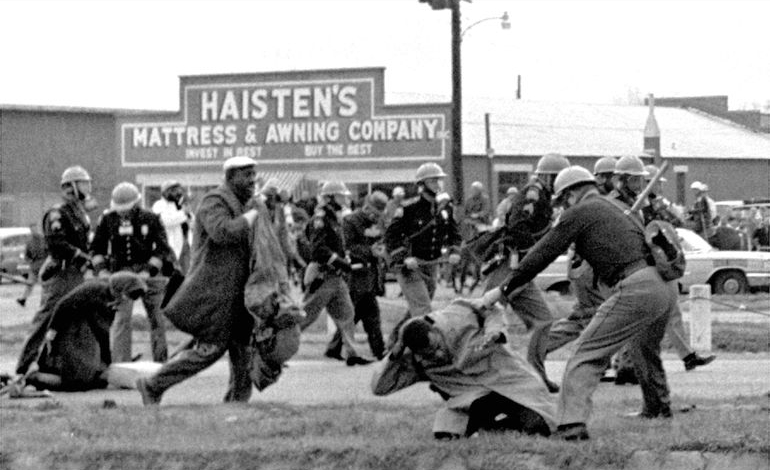

Fifty six years later, in the late days of November 2016, a group of Native Americans tried to move two burned trucks from a bridge in North Dakota. The police said the natives had set the trucks on fire, and they were now too dangerous to move. The natives said the trucks had been lit by infiltrators, and their blocking of the road meant the Ambulance took longer to reach those in need. For attempting to move these trucks, water protectors were shot continuously with a water cannon, tear gas, and rubber bullets, for more than six hours, in weather below twenty degrees.

The next morning, a few dozen people stood on that same bridge, in prayer and ceremony, as police loaded live ammunition, and pointed their guns at our unarmed bodies. As sage smoke surrounded us, a towering man stood in our midst, covered in tattoos, and said the same words over and over again. “Separation. Segregation. Discrimination. These are not the words of our language. Unity. Family. Relatives. These are our words.”

Separation. Segregation. Discrimination.

These are not the words of our language.

Unity. Family. Relatives.

These are our words.

Before the arrival of Columbus, more than 300,000 people lived in what we now call California. Among those people, more than two hundred languages were spoken. Some as similar as French to English. Others as different as English to Chinese. And today, many of our most important books and museums, describe our history in much the same way I originally described Congo. Our country began with a genocidal merchant of death named Christopher Columbus. And progress has continued to grow from that day.

Some historians believe that as many as a hundred million people died, so we could live on this land. Disease destroyed the population, at rates higher than the black plague in Europe. Colonists discovered large tracts of land, already cultivated and organized. Many believed they were blessed beyond measure to stumble into such territory, as they began taking land from a people who had been decimated. Settlers spent the next few centuries, fighting to finish what disease had begun. What was once a thriving continent, connected by rivers and seas transporting goods and traditions, became two masses, divided by borders drawn in European wars.

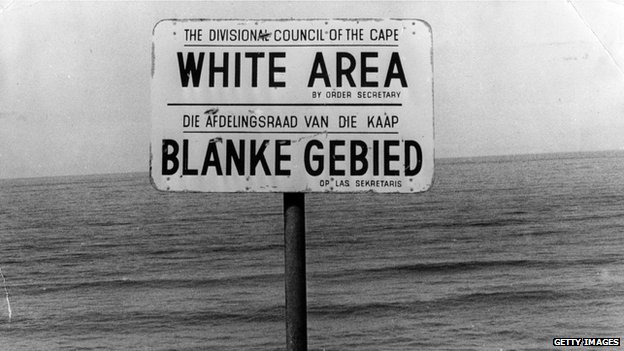

In many countries which have suffered genocide, a generational work is undertaken, toward truth and reconciliation. In Rwanda, commissions went village by village. Mothers forgave their children’s rapists. Killers wept for families they had slain. In Germany, students must learn of the Holocaust, and face their history honestly. Across many parts of Europe, laws mandate the teaching of the holocaust, so future generations can determine for themselves, that it never occur again. South Africa created a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, to begin healing the wounds of apartheid, and move toward what Mandela called “a rainbow nation.” Even Canada and Australia have begun this work, with the indigenous people of those lands. None have been perfect. None have been enough. But in acknowledging the crimes of our colonial past, we become more prescient to those committed today.

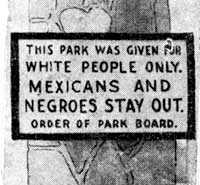

Here in America, we have yet to fully acknowledge what was among the largest genocides in human history. Our Declaration of Independence still holds the words “indigenous savages,” as our constitution still calls those with black skin, three fifths a person. No Amendment can erase those words, or those who died because of them.

Despite their colonial language, generations have revered these documents for their contribution toward human liberation. But centuries before they were written, the Haudenosaunee created the Great Law of Peace. On land that would eventually become the original colonies, the Haudenosaunee built a decentralized republic. By law, rights were endowed by the Creator, and extended to all living things. To the people. To the animals. To the trees. The air. The sun, and the moon.

In many ways, it is the original law of this land.

As Congress acknowledged in 1988, many of the Constitution’s framers were students of the Great Law, and were deeply influenced by its protection of both liberty, and the separation of powers. Also protected, but not imitated, were the rights of women. Grandmothers represented profound wisdom, whose decisions were respected.

Since the colonists first arrived, five centuries ago, we have been building a new project on this land, called America. From the trackers to the train tracks, the frackers to the cattle ranchers, we have measured economic growth in extraction. Only a culture built to survive long winters would measure profit in lumber cleared — but not debt in the destruction of ecosystems and habitats, oxygen production and wind protection, waterways and aqueducts, soil stability and the survival of so many species. This value set has built the modern world. It has accomplished far more than Adam Smith dreamed for. It has also created conditions that have killed half of all living animals in the last century. Extinction rates are a hundred times their normal pace. And today, every living system on Earth, is in a state of decline.

Last year, researchers at Stanford published a study, confirming what has now been said by scientists for two decades - Earth is entering it's sixth mass extinction, and human beings are causing it. Changing this trajectory, will require foundational shifts in how we interact with the natural world.

On election night, I was at Standing Rock, without service or signal. A plane flew overhead every twenty minutes or so, despite the no-fly-zone designation. Though we have no proof, the general consensus was that when the plane flew overhead, phone signals were scrambled. When we were given brief reprieves from its perpetual surveillance and sound, sms messages got through. I remember looking across the river, at a wild array of tipis and domes, yurts and tents, and considering the two choices before us. For while there is little doubt that one choice was a far more destructive choice than the other, there is also little doubt, that both options were colonial. Both options were violent. Both had a vested interest in the continued exploitation of the planet, whether through industries of extraction, the global arms industry, real estate, or multinational financial firms. Both have advocated for tactics that have created more war, more conquering, more death, and ultimately, more colonial power.

In that moment, I gained the smallest glimpse, into what has been true for Native Americans in every election since we began this experiment. There has never been a time when the United States government has not been actively at war with indigenous people. Even today, tribes are in constant litigation, to preserve what little land is left. Their streams polluted, their lands poisoned, and their people perpetually policed. From the perspective of those who have always been here, in each election — from Washington to Trump — all candidates have been violent.

I remember a stunning sunset, in early November, when a young man told me he believes white Americans are the lost tribe. A people without a land. Without a history. Without tradition. He is Dinè, or what we know as Navajo. His people believe they have been in the Four Corners - the land between Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico - for all time. It’s hard not to believe him. Their oral tradition is fifty thousand years old.

He believes there will be great healing, when white Americans begin to rediscover their European past. When we find our family lineage, and learn our history. Before colonizing the world, we first colonized ourselves.

My great-grandmother left my Dad with a few stories, to guide us back to the land she had fled. A few memories, a few clues. At twenty years old, we traveled to Athens to begin our search. The journey we began, has - in so many ways - shaped my life.

My mother’s side of the family arrived here in the 1660s. We were Dutch, and helped form the town of New Paltz, in upstate New York. We then journeyed south to Virginia, and then to Tennessee. Many generations ago, we ended up in Texas. In each of these places, there can be little doubt that we were settlers, and we were colonists. We owned slaves, we sold cattle, we eventually sold oil, and we fought for the expansion of land controlled by white communities. Land that both created our family’s foundation, and destroyed the lives of so many.

The other half of my family arrived on the shores of Ellis Island, just before, during, and after the Holocaust. We are Jews, who fled the violence of Europe, and found a home here on this land. For centuries, our Sephardic ancestors fled persecution wherever they landed. Traveling from northern Africa to southern Europe and the Middle East, we escaped and survived, labored and rebuilt, searching for ways to continue as a people, over and over and over again.

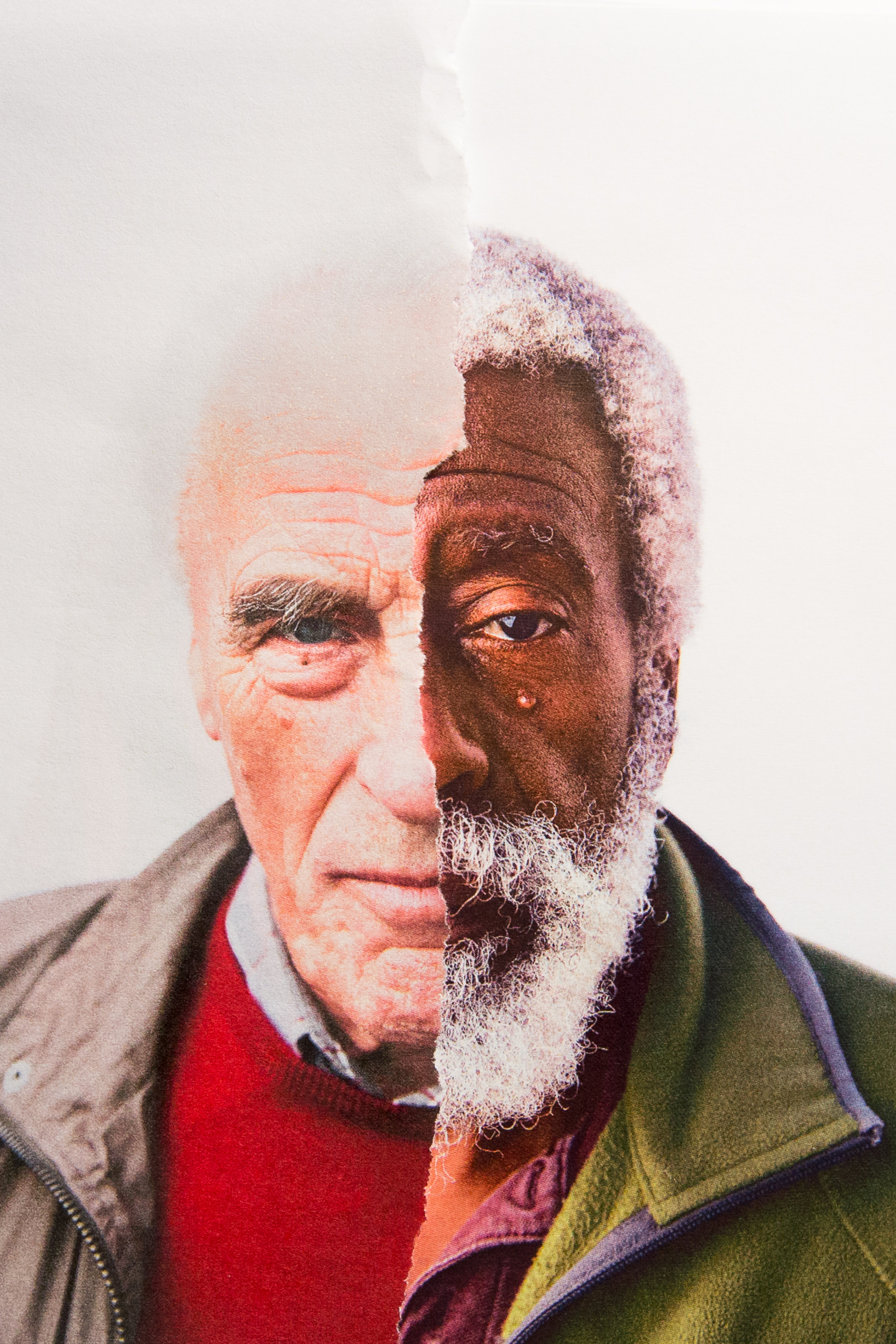

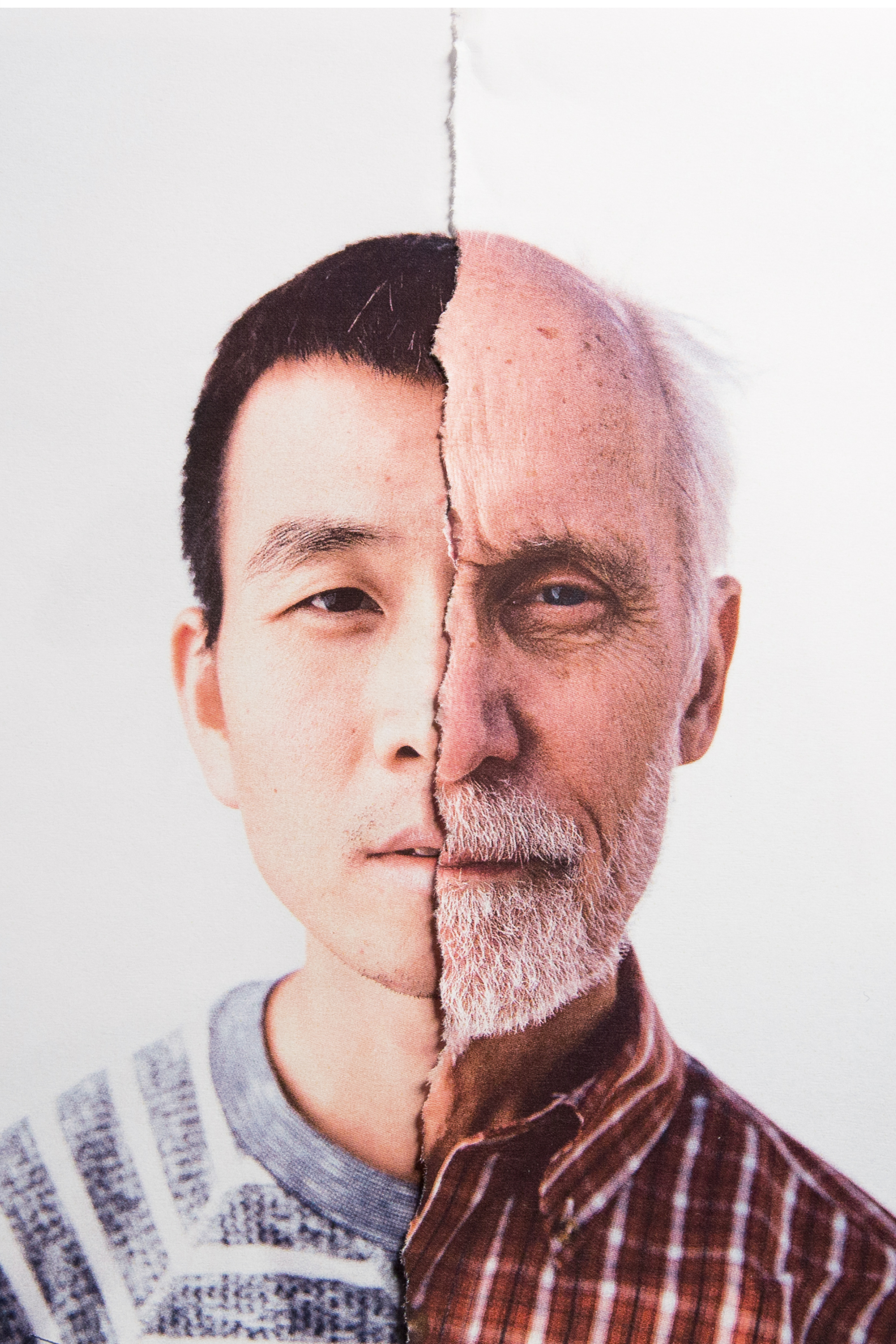

My history pulses through me, as it does for all of us. Like many Americans, I am both the conquered and the conquerer. Both the victor and the victim. The persecutor and the persecuted. Reconciling these pasts within myself, was a prayer shared by many at Standing Rock. To ask forgiveness for our ancestors. To ask forgiveness from our ancestors. To face our history honestly, and find courage in who we must become today. To see our future as one of life, populated by all the colors of the earth.

Regardless of my past, in America today, I am a white man. A white, cis-gendered male. Simply by nature of my racial appearance, my sexual identity, and the class structure I was raised within, I have been afforded tremendous privilege. Though my journey has been fraught with challenges, those challenges have often been quite different than those faced by much of the world. An honest understanding of our history makes clear that our government was built by white landowners, for white landowners. And an honest understanding of our present makes clear; the same is still largely true today. Though I have felt the anti-semitism of good ol’ boy cultures in the south, from the earliest ages, I have benefited from this system.

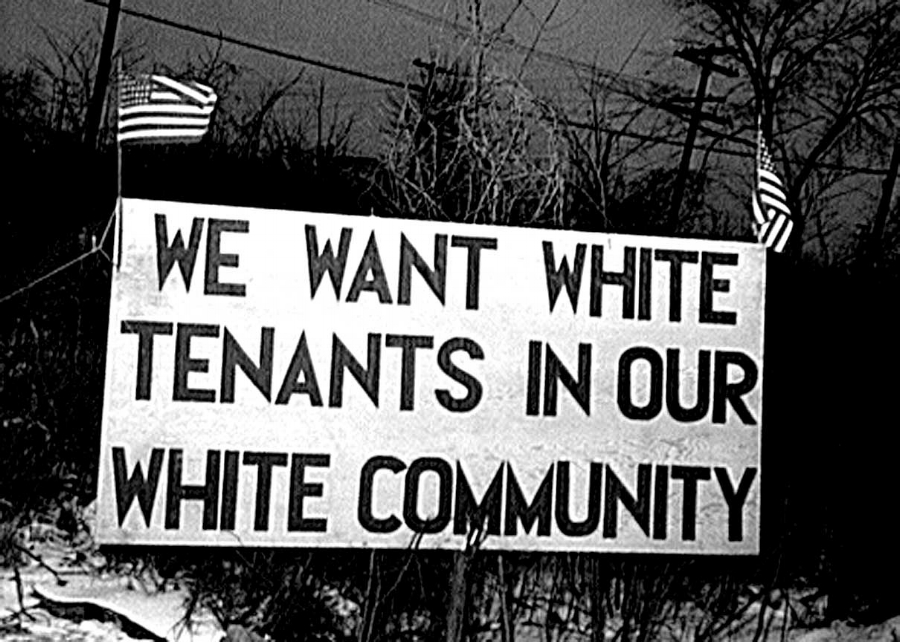

The gap in wealth between white families and black families, is wider today in America, than it was at the height of Apartheid South Africa. The apartheid regime, which may well have been the most systematically racist regime in modern history. And yet our disparity in wealth is wider today here at home, than at the height of their white supremacist power structure. At what point will we begin to acknowledge, that the structure built to enslave Africans for free labor, kill Natives for access to their natural resources, and expel Spanish speakers to ensure white majorities, has never ended. At what point, do we decide to do what must be done, to remove a colonial regime from power. At what point, do we consider a word, deeply dangerous to the prevailing power structure, and boiling up, from the land itself. Revolution.

The landscape of our political conversation is often described in terms of left and right. On the far right, is fascism and totalitarianism. On the far left, is socialism and communism. The American right has protected settler colonialism since its inception. It has manifested itself in hidden and overt white supremacy, patriarchy, nationalism and more recently, outright authoritarianism. Rather than work toward a profoundly different vision for how we structure our society, the elected left of American politics has often been, for lack of a better term, a more inclusive colonialism.

The nature of this debate ensures our conversations are limited to a very specific set of options. As though thoughts can be two dimensional, any more than physical reality can be. But even if we concede a flat spectrum, the opposite of colonialism is not socialism. Or even communism. The opposite of colonialism is indigenous. That most of us have no idea what an indigenous power structure might look like, is but a single indication of how separated we are, from the roots of this land.

The organizers at Standing Rock were some of the finest activists I have ever known. Many were unflinching in their courage, ceaseless in their protection of the water, and deeply committed to the restoration of their community. As we begin 2017 in the midst of international confusion, I am grateful for the lessons they taught so many of us. Lessons of resilience and strength. Of protection and inclusion. I am also keenly aware of their most persistent message — Everything is sacred. The Frontlines are everywhere.

Our current President has declared war. A war on women, Muslims, immigrants, black Americans, native Americans, and the earth itself. Though he is not the beginning of the problem, he is the most dangerous manifestation of white supremacy in a generation. He and his cohorts are as threatened by our wild array of skin tones, as the colonists were in Hispaniola, Congo, South Africa and South Carolina.

Knowing the roots of this struggle, allows me to see the scale at which this colonial regime has corrupted this land. The scale at which we have all become subjugated to a system that is, by its very nature, exploitative.

I spent my childhood summers working on an old quarter-horse ranch. There we learned simple principles, that I have carried with me the rest of my life. Trust through service, & love through labor. While the different camps of Standing Rock were run with indigenous leadership, in matters of labor, every hand was welcomed. White hands could cut firewood, as well as Indigenous hands. Black hands could build shelters as well Latino hands. The tension between races was real, as was the reconciliation that happened through a shared need to survive the winds of the Great Plains. The ongoing conversation was one that challenged settlers to reconsider many of the assumptions we were raised within. And challenged a chasm between settler and indigenous, that has grown wider with each successive generation of oppression.

One night around the fire, we were told that the original settlements posted sentries — not to protect from the outside — but to keep people in. For while those who led the excursions and established the camps were endowed with wealth or sponsorship, many of those aboard were brought as laborers, servants or slaves. Many plotted to escape the hunger, disease and poor sewage of the settlements, and live instead in the nearby communities that already existed. Systems had to be put in place with great urgency, to control the population being brought here, and keep them from uniting in rebellion, or leaving the European settlements all together.

What has been called the four horseman of civilization; a judge, policeman, taxman and a lawyer, became the cornerstones of our foundational institutions — the courthouse, jail, bank, and a house of edicts. This web of debt, penalties, punishment and the perpetual threat of force, were utilized as forms of control. No myth was more powerful in enforcing these institutions, than that of racial hierarchy.

Resistance to these hierarchies, and these institutions, is as old as their claim to a monopoly on legal violence. While the history of indigenous heroism, maroon colonies, red and black solidarity, and defections of whites, has been as erased as the history of resistance in Congo. As the African proverb says so clearly; “until Lions learn to write, tales of hunting will always be told by the hunter.”

Though there were many challenges, and deep abiding frustrations, Standing Rock offered white Americans a chance to begin standing on the right side of history. A new generation of indigenous activists appear ready to explore that possibility further. If the mistakes of the past provide any insight, my sincere suggestion to all of us who have settled here, is we begin, with listening. Learning. Serving. Reading. Then listening again.

I saw white people help build a school for indigenous children. A school that may well shelter a generation, built with their hands, from clay and straw. Saw white people build shelters, and gather supplies, and clean dishes, and serve elders, and do all the things that were necessary for camp to run.

I also saw white people display ignorance, in situations that demanded reverence. And center themselves, when the occasion called for them to step aside. Such a criticism could well be made of this piece.

We learned through experimentation, and open conversation, to find ways to live together. To reconcile our differences, at least enough to carry on with the necessary tasks of each day. It wasn’t perfect. It never is. As time went on, many white folks learned to weaponize white privilege with authorities. To place our white bodies between law enforcement and Natives, while they stood in prayer, defiance and protection. The strength and poise of those who led the daily actions, inspired courage from all who followed.

There is an opportunity in our time, to do what previous generations have not done. To leave the settlements of our minds, and begin working with those who protect the land. If we are to pick a side in the United States of America, let us pick the side of life.

Though the context is different, it is worth stating the obvious, in that India is no longer run by the British. India is run by Indians. Just as South Africa is no longer run by the decedents of the Dutch. South Africa is run by South Africans. Though Europeans continue to own many industries in former colonies around the world, and European power structures are often emulated, most countries have at least symbolically transferred power away from the colonizers, and toward those who had been colonized. While the American power structure is still largely controlled, by the descendents of settlers.

As I consider our current state of affairs, I am reminded of San Miguel de Guadalupe. Of who we were, at the beginning of our continental collisions. When Europe, Africa and the Americas first met on these shores. We were a wilder people then. All of us. It was a wilder time. But America was free. Long before the Europeans or the Africans arrived. This land was vast and alive and the people who have always been here were then, as they have always been, free.

Perhaps I’m late to the table. Perhaps something new is just beginning. Regardless, I’m here now. Here for the end of patriarchy. Here for the end of white supremacy. Here for the end of colonialism. The people living on these connected continents must begin to stand together, for the preservation of our collective future. For the earth. For the rivers. For the air. For our children, and their children’s children.

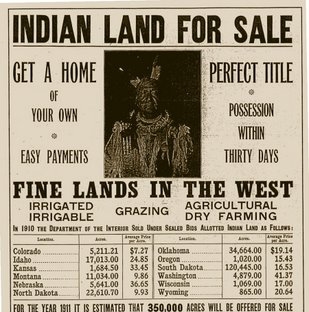

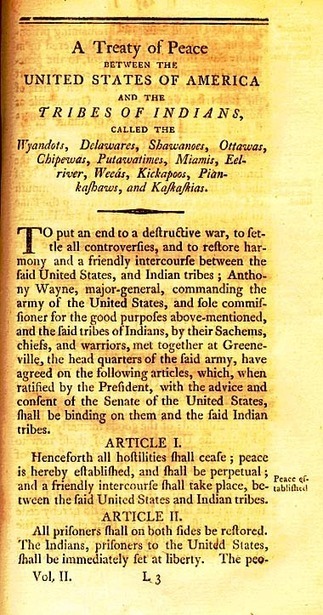

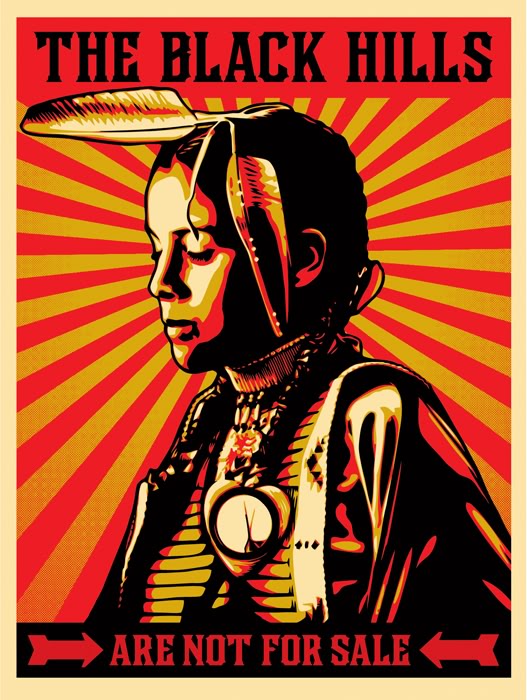

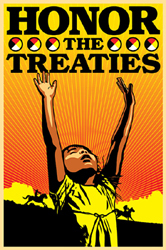

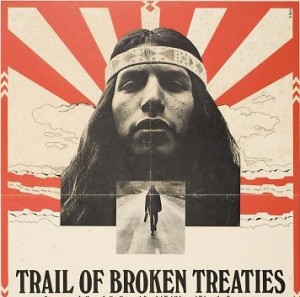

It has been said that the only way to restore America’s vast farmland, depleted by decades of mono-crops and pesticides, is to return the ancient grazing lands of the Buffalo. Their hooves are designed in such a way, that the wild herds naturally till the soil. Of course, the only way to create such a large territory without the fences necessary for cattle, would be to return the Treaty Lands originally promised to Native American tribes, and signed into law with the United States Government. Treaties forged in war. Treaties won in battle. Treaties which are, according to the United States Constitution, the “supreme law of the land.”

If there is to be a revolution in this land, let us begin with the Treaties. More than five hundred agreements signed by the same government we fund with our tax dollars. More than five hundred agreements which have been betrayed.

These kinds of dreams feel far from the urgency of the present moment. Neighborhoods are being raided by ICE Police, and sent to for-profit deportation centers. Public schools are being threatened in all our neighborhoods, black and white, rich and poor. An attorney general has been appointed who lied under oath, and who Corretta Scott King said will do “with a federal prosecution, what the local sheriffs accomplished twenty years ago with clubs and cattle prods.”

Even as the pulse of revolution roars across this land, my sense is that many of the answers will ultimately be found, in the land itself. In rediscovering our true history. Paul Hawkins is an ecologist, who believes the earth possesses a unique intelligence, and is working with all of creation to guide life forward. In what he describes as “the largest movement in human history,” he suggests that if the earth is a living and breathing organism, perhaps the activists rising around the world, are her white-blood cells. Rushing from infection to infection, working to restore life itself.

While we must resist the current regime, protect one another no matter the cost, and work to dismantle a system of violence so pervasive it controls even our water — there will be another task at the end of this work. That task will be in truth and reconciliation. In listening to those who have been desecrated, and working toward restitution. Toward reparation. In acknowledging that all the land we place our feet upon, was stolen in genocide. That all the trees we kill to build our homes and towns, were stolen in genocide. That all the rivers we pour our waste into, and the lakes we enjoy on vacation, were stolen in genocide. That there have been vibrant and thriving communities here for a millennia, and they are our true founding mothers and fathers.

Until we acknowledge this truth, we will continue to be unable to face the reality of who we are. Of what our power structure does to people around the world. We will continue to be unable to see the racism that drives so many facets of our global economy, or the insanity of borders that benefit the majority race, at the expense of everyone else. Unable to face the consequences of violent regime change, and a war machine that profits from the vast exploitation of people and planet. Unable to face the fact that we fund it with our daily lives.

We know from those who have suffered trauma, that when something is ignored, it gets worse. Like a tumor, spreading from one aspect of our lives, to another. Among the many lessons of Standing Rock, was that we cannot continue to ignore this, the gravest of deceptions.

In facing our colonial past — and our colonial present — we will likely have to face the laws of nature; laws that have guided this land for a millennia. Laws governing the rivers and aqueducts. The forests and fungi. These laws are ungovernable. They exist independent of policy or proclamation. I am convinced that such is also true of natural rights. Of the rights of life. Of the basic protection of human dignity. When foundational human rights are not protected, we too should be ungovernable. Uncontrollable. Unyielding. For what is more American, than challenging power held unjustly.

The work before us is immense. I’ve spent much of my adult life working alongside activists, dedicated to creating a more just, and peaceful planet. In a democracy, the tools of advocacy are well known. Originally pioneered by the Abolitionists of England, tactics such as petitions, boycotts and demonstrations, have long been weapons in the arsenal of activism. They are tools I have worked with alongside many others, and tools I have seen challenge power to do more for the marginalized. At Standing Rock, the descendants of this land transformed those tools into a living, breathing, community of resistance. Every day, we woke up to serve the movement. We went to bed, tired from serving the movement. In creating shelter for one another, we served the movement. In delivering food to the elders, we served the movement. In taking out the trash, we served the movement. Among a community built on service, and an economy built on sharing, were hundreds of bodies, ready and willing, to challenge both State Power, and an industry of extraction. Hundreds of human beings, who could be mobilized at a moment’s notice, to protect the land, and defend one another.

This community existed both within the state, and separate from it. While we used money to buy materials, at camp those materials were generally shared and traded, for friendship and service. While we were under the constant surveillance of the Morton County Police, the security at camp was run with indigenous leadership.

I remember being initially jolted by the site of the stars and stripes, flown upside down, below a tribal flag. It was a site seen frequently throughout camp. As I learned more of those who flew the United States flag in such a way, I did not find anger or hostility. I found a deep love of this land, and the people who care for her. Along with a deep, focused rejection of a regime that has perpetrated a genocide upon their people for centuries.

The Dakota Access Pipeline runs through land that was originally dedicated to the Lakota and Dakota people, in the 1851 Treaty of Ft. Laramie. The treaty would be broken over and over again, with each successive agreement reducing the lands in which they could hunt and grow food. None would take more land, than a series of dams built by the Army Corps of Engineers in the 1940s and 50s. Though careful consideration was made to ensure settler communities were left undisturbed, the project would eventually flood Native territory, and destroy the vast majority of timber land, range land, and land used for gardening and agriculture. Thousands of families were displaced. Many died. Today the reservations that resulted, are often described by those who live there, as POW camps. If they were anywhere else in the world, they would be camps for IDPs. Internally displaced people.

Since the 1940s, the Army Corps has leased or sold vast swaths of the land claimed in the floods, to cattle ranchers and farmers. Driving toward the reservation, large cattle ranches show the generational wealth that has resulted from this land grab. In many cases, these are the same ranchers who are then leasing the land to DAPL. Government wins, cattle industry wins, oil industry wins. All that’s needed, is to erase the mass displacement of entire populations.

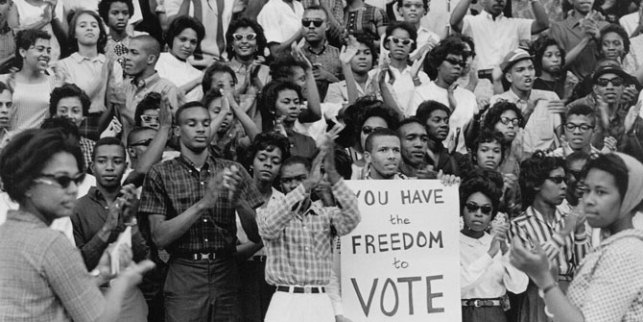

For the colonists, democracy continued to be a brilliant solution. Perhaps the greatest irony of the system we have advanced around the world, is that while it purports to deliver freedom, the end result is in ensuring permanent power for the majority. Flood the land with those who look like you, enslave and attack those who don’t, and maintain a majority at all costs. But what of those whose ancestors paved the original trails from sea to shining sea. Those who have been decimated by war and massacres, starvation, boarding schools, and the abduction of generations. Are they meant to live in perpetual powerlessness, because their communities are often too small to win elections?

How do we reconcile a European revolution rooted in property rights, with an indigenous tradition that often finds the word “property”, as repugnant as any racial slur. A word that infers ownership, over that which cannot be owned. Is it any surprise, that we have worked so hard to discredit and destroy traditions, rooted in protecting the earth we wish to sell.

If there were ever a challenge for our time, it would be in utilizing the fullness of human imagination to create a new system, to organize this land. To build a place that truly protects life, liberty and justice for all. To write new founding documents, that reflect our ancient past, and the journey that has brought us to this place called America. To create an America, for all Americans.

I do not know what is ahead. If history offers any lesson, resistance to authoritarians is often a work fraught with failure. Filled with suffering and sacrifice and perseverance and loss. Until it isn’t. Like those who broke down the Berlin Wall, there are periods when nothing seems to change at all. Until the great wells of human spirit are pierced so thoroughly, that a flood of resistance and courage bursts forth. It is in these great storms, that human liberation has been won. The fights before us may feel nearly impossible. Who are we, the thousand million, who simply desire a chance to raise our families in health and liberty. We the powerless. We the workers. We the creators. We the elders. We the children. We the free. We are little more than a drop, in a great storm of injustice. In the moments I begin to drown, I find myself asking a question the abolitionists once asked — what is an ocean, but a vast community of drops.

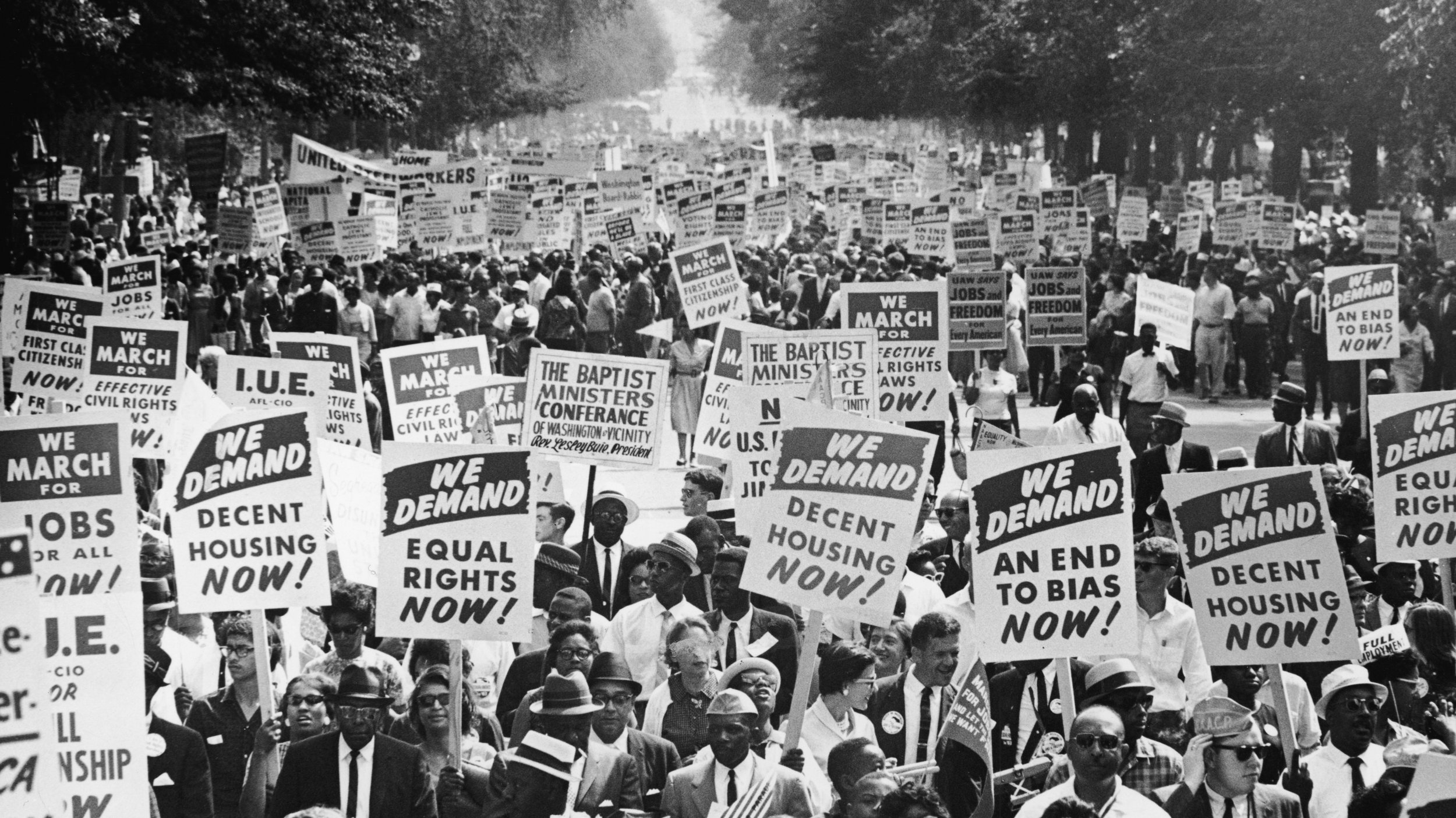

The time for half measures may well be over. The internet era has unleashed a dizzying array of tactics for modern resistance, from rapid response protests to instant petitions. Each of these should be utilized to the fullest extent possible, and the larger movement will grow by being continuously open to new tactics and technology for resistance. But transforming our country will require more than the tactics of advocacy. It will likely require mass demonstrations, on levels previously inconceivable. Communities of resistance, working full time, to protect our neighbors. Divestment, from all institutions that fund human oppression. And a decentralized network of nonviolent civil disobedience. Across oceans, cultures, borders and wars, humanity will have to rise for our most basic rights.

There is a great deal to be done. The immensity threatens to overwhelm my senses. But then I take a deep breathe. Many deep breaths. And remember that this had to happen. This ugly system had to finally manifest itself in this ugliness. This racist system had to finally manifest itself in this racism. This deadly system had to finally manifest itself in this march toward war. Some have always known that this is who we are. That this is who our power structure is. Now a great many of us know. Now we can get to the real work, of mass resistance. The work of dismantling systems of violence. The work of rebuilding communities. The work of restoring ecologies. The work of communication and trade and trust and exchange and the protection of all that is sacred. Of interdependence. This is the future we must build. It seems that first, we must face the fires of a regime exposed. Just as our ancestors did.

It is okay to be afraid. I am afraid. But we must find within ourselves all remnants of courage. We must add air to those coals, and flame them to a roaring fire. This is the work of our lives. It will happen in small ways — within a cabin, or a child’s mind. And it will happen in large ways. We must be here for it all. To stand for what is right and just. To bear witness to all that is not. We will falter and find frustration. But we will persevere. And we will work to protect all that demands it. I love you all. The future is for the living, and the earth is on our side.

Sean